Speed and Spread

The power of computation has become the motor of history.

Ambient Computation

In Faster than Nature, I showed the Enlightenment cracking open Christianity’s apocalyptic time, sending it on a new trajectory. Time, no longer under God’s control, became open-ended and driven by multiple natural processes that we could seek to control.

As our understanding accelerated, so has our influence. To borrow Michel Serres’s line, ‘we are steering things we didn’t used to steer.’

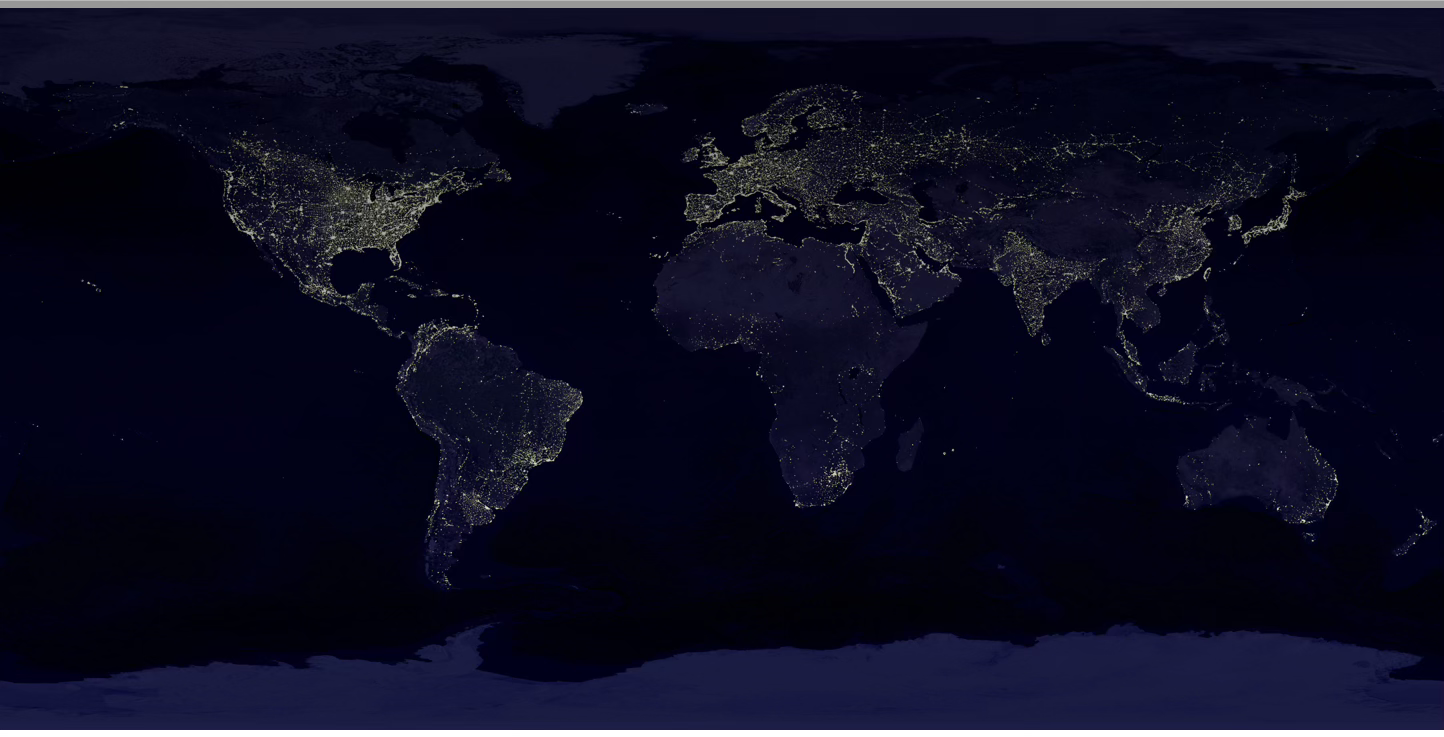

In a mere 300 years—roughly .2% of Homo sapiens existence—we have wrapped the Earth in our technology, extending the speed and spread of our actions at a pace unimaginable at the beginning of the Enlightenment.

For much of our time on Earth, what lay beyond our control was folded into the idea of fate—the will of the gods, magic, or nature’s inscrutable forces. The Enlightenment recast this vision. We began staring into that opacity and learning how to make it tractable—something we could understand and eventually steer.

This essay follows that legacy forward: how computational power became the motor of history.

I’ll start with an episode in my own life from 1995.

Computational Entanglement

I entered the software industry (May 8, 1995) during a crisis of time. A decades-long, cost-saving engineering decision was about to become an apocalyptic bug: clocks embedded in our systems would jump back a century at the millennium.

No one knew what would happen when time suddenly went out of joint—when January 1, 2000 became January 1, 1900.

Amid the uncertainty, some Americans stocked up on food, water and guns in anticipation of a computer-induced apocalypse.1

It was a crisis of miscalculated time. We’d built clocks that couldn’t count centuries, and their longevity far exceeded their makers’ expectations. As Alan Greenspan admitted in 1998:

It never entered our minds that those programs would have lasted for more than a few years.

Y2K’s apocalyptic mood wasn’t a quirk of the emerging digital age. It marked how deeply computation had entangled itself with everyday life.

We were Being Digital, as Nicholas Negroponte put it.

If only word processors or spreadsheets were at risk, no one would have predicted catastrophe. But computational power had become infrastructure and was shaping the very structure of time.2

This didn’t happen overnight. Entering the industry of Enterprise Software in 1995, fresh from Infrastructures of Enlightenment, I felt I’d stepped off eighteenth-century roads and onto what Al Gore was calling the Information Superhighway.

The infrastructure was threatening to undo itself, and us, by miscalculating time.

Read more about Our Computable World at Time as Practice.

Reformatting the World

I found myself in the latest chapter of a long history in which humanity was learning to use computational power to shape the rhythms of life. We were rendering more and more processes tractable—and therefore dependable.

That dependability now appears mundane. Amazon tells me my package will arrive between 4:00 and 7:00 a.m. A GPS predicts my arrival at 1:36 p.m. within a minute or two. These aren’t guesses; they feel like guarantees. We have formatted the world through scalable computation so that time behaves this way.

We would be mistaken to think computational power is an external force imposed on a passive world. Its speed and spread follow from a deeper fact: nature itself has a structure that can be computationally modeled and steered.

As theoretical physicist Sara Imari Walker writes:

That our technology can capture such a deep regularity of nature and use this knowledge to cause things to happen is a highly nontrivial feature of our universe.

She echoes David Deutsch: only stars and intelligent beings who understand stellar processes can turn base metals into gold. Steering becomes possible because technology and nature share a common bond; they have a similar computable format.3

The Enlightenment was the moment this bond became an object of systematic inquiry. Natural processes—heating, cooling, gravity, population growth, food production, spread of disease—were rendered calculable, opening them to projection, anticipation, and deliberate intervention.

New roads, imperial shipping lanes, railroad tracks, telegraph lines, and the adoption of Greenwich Mean Time formed an engineered lattice that synchronized people, goods, time, and communications at unprecedented speed and scale.

History’s movement began to take shape as the intractable becoming tractable—nature revealing its own computational power, which we have learned to steer.

Calculating Time

We can see the emergence of the Enlightenment’s tension between tractable and intractable by watching how calculation reshaped humanity’s sense of time. The shift was not linear but a slow turning in which multiple temporalities coexisted uneasily.

Consider three moments.

Three hundred years ago, God’s creation was still reckoned at roughly 6000 years old. When Newton placed creation at 3998 BCE, he was following a method of Biblical calculation established more than a millennium earlier. Yet when his own heating-and-cooling equations suggested a 50,000 year old Earth, he rejected the result. Time, he felt, could not be that far out of joint.4

Enlightenment geologists stretched this chronology. In 1774, George Louis Leclerc (the Comte de Buffon) calculated how long it would take the Earth to cool to its present temperature:

… one finds that the terrestrial globe will have solidified to the centre in 2,905 years approximately, cooled to the point at which one could touch it in 33,911 years approximately, and to the present temperature in 74,047 years approximately.5

Like so many Enlightenment geologists, Buffon was trying to reconcile Genesis with physical evidence. But these calculations were forcing humanity to come to terms with a time that couldn’t be contained by 4000 BCE.

Biblical and geological time scales competed well into the nineteenth century. Reading Enlightenment geologists, we witness Biblical time unraveling as the slow movement of nature’s processes places time in a new light.

James Hutton made this explicit in The Theory of the Earth (1788):

The Mosaic history [the Old Testament] places this beginning of man at no great distance…. But this is not the case with those inferior species of animals…. We find in natural history monuments [fossils] which prove that those animals had long existed; and we thus procure a method for the computation of a period of time extremely remote, though far from being precisely ascertained.

If Buffon’s and Hutton’s computations stretched the past, Thomas Malthus (An Essay on the Principle of Population, 1798) reoriented calculation toward the future. His model of exponential population growth versus linear food production forced humanity to reckon with a fate that could be calculated:

Taking the population of the world at any number, a thousand millions, for instance, the human species would increase in the ratio of —1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, &c. and subsistence as—1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, &c. In two centuries and a quarter, the population would be to the means of subsistence as 512 to 10…

Malthus’s figures modeled a future demanding intervention. If we could learn to steer nature’s processes—improve soil, transport more rapidly, restrain population—we could drive history in more advantageous directions.

Malthus remained pessimistic, seeing moral restraint as the only defense against a calculable fate. Still, his calculations showed that the opaque motions of nature could be rendered computable—and, once computable, open to deliberate redirection.

Natural and Artificial

To think we impose computation on an otherwise uncomputable world is to flirt with a false divide between the natural and the artificial—as if they were mutually exclusive categories, so that ‘when they clash,’ as Lee Smolin writes, ‘a choice must be made between them.’6

It’s a false choice, one that obscures how computational power sets the direction of history—for better and worse.

Everything belongs to nature, including what we label artificial. Computational power is real power. It works because it aligns with nature’s causal structures, just as we do.

This, too, is an Enlightenment legacy: our technologies are aligned with nature, even when they are not allied with it.

We compute ways to slow aging and elongate life because we understand how they work. AI’s and LLM’s modeled on neurons and synapses generate outputs far faster than any one of us can. We read the genome’s code and edit its sequence to our specifications.

If we are steering things that we didn’t used to steer, it is because we have been reformatting the world so that we can steer it. But this only happens because science, technology, and nature’s processes are not different in kind, but only in degree. This alignment allows more and more of life to become tractable to computation—at great speed and scale.

The history of this alignment has moved quickly in the grand narrative of Homo sapiens.

1870’s: Harvard’s Observatory lays cable throughout New England and sells ‘Boston Time’ as a service—sending precisely sequenced electrical pulses to synchronize far-flung clocks. Subscribers included cities, railroads, and high-end jewelers wanting to show off the accuracy of their watches.

Time as a service is born along with an annual recurring revenue model.

1884: Greenwich became the center of world time; in the two preceding decades, telegraph cables stretched across the globe in an effort to create more accurate measurements of latitude and longitude:

By 1880, ninety thousand miles of mostly British cable lay on the ocean floor, a ninety million pound machine binding every inhabited continent, cutting across to Japan, New Zealand, India, through the West Indies, the East Indies, and the Aegean… For through copper circuits flowed time, and through time the partition of the worldmap in an age of empires.7

Y2K warned us that we had better pay close attention to our engineering decisions because we were embedding the speed and spread of computational power into our lives. Greenspan again: ‘It never entered our minds that those programs would have lasted for more than a few years.’

We had taken over time itself as a computable output—as the synchronizing of clocks and the actions they coordinate—and we got it wrong.

We have made computation into the motor of history. The Enlightenment has accelerated to the point where we must ask: Do we have the capacity to steer with purpose? Can we recognize the accursed shares that inevitably arise from our good intentions—without abandoning those intentions altogether?

Can we master our own capacity for mastery?

For a deeper dive into these issues, see The World as Computation on Time as Practice

Francine Uenuma, ‘20 Years Later, the Y2K Bug Seems Like a Joke—Because Those Behind the Scenes Took It Seriously’ Time Magazine, December 30, 2019.

The Year 2000 Problem (Wikipedia) documents a number of Y2K events that are infrastructure related.

Sara Imari Walker, Life as No One Knows It, 142-3. David Duetsch explicitly claims this Enlightenment legacy. The Beginning of Infinity shows how the power of better explanations became the motor of human progress during the Enlightenment. It is also important to note that it remains an open question as to whether computation is fundamental to the universe or an emergent property of local systems.

Stephen Toulmin and June Goodfield, The Discovery of Time, University of Chicago Press, 1965, 146-7.

Quoted in Toulmin and Goodfield, 147.

See the Epilogue to Time Reborn for Smolin’s argument for why we need to ‘think in time’.

Peter Galison, Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps: Empires of Time, Norton 2003, 144.